I've been busy

The Staircase

Not that you need to be told this but no, you don't need to write every day.

Someone published a "writing advice" article about how you need to write every day otherwise you are a fail or whatever. "Write every day" is one of those perennial things which appears in writing advice nuggets. I don't believe in that piece of advice, and not just because that method doesn't work for me.

I used to feel guilty about not writing every day, or having long stints of time where I am not writing and am instead binge watching Friday Night Lights on Netflix (which I've already seen) or engaging in my endless search for a lobster necklace on Etsy. Then I did the math on my productivity. It takes me about 6 months to write a novel. Just the draft. Which I then put away, then rewrite however many times. But the actual bulk of the work takes 6 months, which is a decently fast clip. I'm new to novel writing--most of my writing life has been spent as a short story writer. I tended to think about stories a lot before I ever sitdown to write them, so when I did finally sit down, they more or less come out in one long stream. However much time I have to type that day, that is. Similarly for novels, I work out my plot outlines and just plow through it.

Which means I have a high amount of productivity during a short burst of time, then a word desert for weeks or months. You know what though? My productivity is fine.

I can't find the article, but when I was training for a long running race, I read something by a marathoner who said that his absurd finishing speeds (I don't know--anything less than 12 hours seems fast to me--but I think it was 3 hours) were not hindered, but actually helped by the fact that he took breaks to walk. This goes against logic in some sense, how can going slower help you go faster? Even when you're doing it during a race, you feel a pressure to start running again because people are passing you. A guy dressed like the Statue of Liberty juggling three balls is passing you (yes this happened to me.). Ultimately, taking walking breaks became a structured way for me to complete races in increasingly faster times.

Similarly, I'm a weight lifter and anyone who lifts weights knows that you can't work the same group on Monday and Tuesday. Lifting causes tiny damage to your body--you need that time to recover. And protein in the form of mediocre-tasting powder-based drinks. Lifting more is not lifting better if it results in your being injured, or working inefficiently. More is not better. Ask anyone who does interval training.

I get the sense that "write every day" might be something that some people need to be told in order to get their butts in a chair, because otherwise, they won't write. Well. . . if you need to be shoehorned into doing something, maybe you don't really like doing it? Yeah writing involves some components that you don't like--maybe it's revision. Maybe it's copyediting. But at some level, you should want to work sometimes, and you should be able to without having a rigid structure imposed on you by some arbitrary guideline. Often people lament that they don't "have the time" to write because [insert whatever]. Jobs. Kids. No quiet space. But the fact is that people with jobs, kids, and loud spaces all find a way. They learned to write in small bits of time they did have, or when the kids were screaming. They did it because they wanted to. And the shape of how they did it differed.

Do what works for you. If it's not working, stop. "Not working" can also mean not hitting the quality goals you want because you're burning yourself out. Things that are "not writing" are actually writing: targeted reading, reading for pleasure, going to readings, admin stuff like sending to magazines or researching agents or publishers, consuming things--which includes TV, movies, meditating, running, baking, or whatever puts you in a thoughtful mood.

Why I Hate(d) Present Tense

I'm not a huge fan of creative writing that's in present tense; it has its time and place, but I'm of the opinion that it's overused. If present tense writing is done well, you don't even realize it's in present tense; when it's done badly, it sticks out and is often jarring. Past tense has been the default for so long that it's naturally invisible in most cases.

(Kind of an aside, but one could argue, if present tense is invisible if done well, and past tense is invisible regardless, why pick the former over the latter?)

The primary argument for using present tense is "immediacy," in the sense that you are right there along with the character, seeing everything unfold minute to minute. I would argue that the primary reason for just how much present tense writing there is out there right now has less to do with immediacy, and more to do with what happens to be in style. I have written in it before, and still do occasionally, but my own default is past tense and I find myself irked when I'm reading something in present tense that does it badly. (Another peculiar thing is how often you catch a writer writing in present tense lapsing into past tense.) While there are present tense genre books, as someone who passes between genre and literary fiction, it seems like there's way more present tense being used in literary fiction. I think this is because it was solidified as part of the hyper-realistic style that dominates in litfic that we were all taught in creative writing classes from emulating the classics (see: the post WW2 white writers, typically males) Present tense "sounds" more literary, in part because on a line-by-line basis there's something that makes it sound different than "standard" storytelling.

Good present tense writing is immediate and never jarring. But oftentimes when it isn't done so well, it isn't immediate at all, is sometimes grammatically confusing (or just incorrect), is often dishonest; in which case you'd think, why not just write in past tense? (whisper: because it isn't literary..)

Historical present tense

Historical present tense makes the most sense to me. We lapse into colloquially when we're talking about something that's already happened, e.g., "So I met up when them, and like, I go in, and everyone there is wearing rabbit ears, and I'm like, what?"

a strange recurrent instance of Bart Simpson speaking in historical present tense.

It works well for things that are extremely grounded in moment-by-moment details:

JFK and Jackie are sitting in the back of the convertible, waving. Suddenly he jerks forward, grabbing at his throat with both hands. People scream. The car speeds up.

Although really, I could argue, is this that different from:

JFK and Jackie were sitting in the back of the convertible, waving. Suddenly he jerked forward, grabbing at his throat with both hands. People screamed. The car sped up.

Minor lapses in immediacy... Forgivable, or moral travesty?

Here's where it gets weird, at least for me. Take the following conversion from simple past tense to present tense.

The dog barked all afternoon until someone took pity on it and let it out.

The dog barks all afternoon until someone takes pity on it and lets it out.

The first sentence, in simple past tense, actually has two senses of time: a longer period where the dog is barking, and then a more specific time point when someone lets it out. (You could also convert this to present perfect tense: The dog had barked all afternoon until someone let it out. In proper usage "had barked" is someone that occurred in the past-past until someone interrupted it--letting it out, which is in simple past. I can't imagine that there is any reason for past perfect tense even existing except for the fact that humans have been telling stories in past tense for centuries and our language developed that way.) The present tense sentence violates any sense of immediacy to me--because of that span of time, I'm not "in the moment," I'm summarizing over a series of moments. That sentence probably doesn't bother a lot of people, but I'd argue that it's more of a stylistic choice, than a choice made because it is more immediate. "Immediate" should be point-by-point, like the JFK example.

Major lapses in immediacy

Sometimes you need to summarize over large swathes of time. This is fundamentally "telling," and has to occur sometimes in regular writing, and in exceptional writing can be just as captivating as "showing". (See Italo Calvino or Gabriel Garcia Marquez). Take the following three examples in, respectively, past tense, past perfect tense, and present tense.

Mordor recruited troops from distant lands for ten years before marching on Osgiliath.

Mordor had recruited troops from distant lands for ten years before it marched on Osgiliath.

Mordor recruits troops from distant lands for ten years before it marches on Osgiliath.

The marching on Osgiliath part is the most "immediate" part here. You're not "there" as much with the ten year recruiting part. In the JFK case, I'm literally describing the second-by-second of the Zapruder film. With past tense, in some cases summary is merely background information that provides context for the more important, immediate part of the sentence. In other cases, it is a thing unto itself: the thing you are describing is so large across space or time that it can't be handled except in summary (e.g., the descriptions of the progress of the Civil War in Gone with the Wind) or you are for stylistically referring to something "large" in simple terms ("The universe expanded" or "Rome fell." --this reminds me of Kurt Vonnegut.) The reason that present tense doesn't work well for summary is that lack of immediacy (this would be the part of the movie that is a montage of ten years of recruiting troops, as opposed to moment-to-moment), but also the timeline getting messed up. Mordor can't be recruiting (for ten years) at the same time it is marching on Osgiliath because both are in present tense. Unless you want to say that ten years passes after you read the word "years." This is weird.

Present tense memoir?

If you think of it, memoir is composed of four separate things: 1, a personal recounting of something that happened, 2, a best recollection of one's emotions at those points in time, 3, time-of-writing reflection on those events, and 4, time-of-writing emotions about those events. Human memory is very much fallible; memories are constructed more than they are recalled like videotape that is played back. 1 is hard enough, and I find it hard to believe that 2 is really 2, and not 3 and 4 influencing 2. I find it hard to believe that they don't. To write about what happened to you in the past in present tense, for the sake of immediacy, is to ignore that all the time that passed between then and now isn't reflected back in that writing. As if it isn't altering the very way you tell the story itself. This view may be extreme. I don't care, I'm just writing random shit on a blog.

One thing that more justifiably drives me crazy: extensive summary and violation of one's own personal timeline in memoir. Take the following:

It's Christmas. I am unwrapping my three presents: a yo-yo, a watercolor set, and a My Little Pony with long eyelashes. My family does not have a lot of money.

So far so good. Not really though--the yo-yo promptly broke. But then:

In 1970 my parents meet in Bombay at a tea shop. They are different castes. They get married and move to America.

Wait a minute. I wasn't even alive in 1970. Worse still:

In 1978, I am born.

Dude. No. Not unless you are David Copperfield. There is no immediacy to the moment of my birth. I have no memory of it. Changing the words and content around, I have seen this in personal memoir and it makes me want to gouge my eyes out. These things are subjective and things will move in and out of style.

For the love of god what does future tense in present tense even mean?

Again, this is referring to memoir. It drives me crazy every single time because sometimes there isn't context to understand whether the meaning is literal or figurative. Example:

My fifth year into my PhD program it occurs to me that over the rainbow, there might not be a job. I study statistics. I do some schmoozing networking even though I don't like it. I will get a job.

Does "I will get a job" mean that literally, in my future a job will be there? In other words, in the past (told in present tense) I am saying that I know (in the future) the fact of what will occur (that I will get a job.) I don't know, isn't that motherfucking cheating? Or is the statement "I will get a job" more figurative, like me making a declaration of will or intent. (Which, literally, every time I think about this issue, makes me think of the below scene from Wayne's World.)

In sum, if your writing reminds someone of Wayne's World, you have probably failed.

Data Dive: Grin and Bear It

This was my first and only piece of nonfiction. It's been a couple years since I wrote it, and I've had a lot of time to reflect back about those events. It was selected for an anthology of DC-based stories published annually by Politics and Prose, an awesome independent bookstore which is an establishment in this city. I do feel this was the best home for this story and am pleased to be included in a collection with other DC writers. They held a reading for the rollout of the anthology and I attended it with Sarah (the one mentioned in the piece.)

If you're curious about the pandas, it really was a stupid big deal..

Becky Malinsky/Smithsonian's National Zoo

Pandas are so stupid. Exception:

Number of submissions: 8. Ratio of positive feedback to number of submissions: 25%. Time from completing story until publication: 1 year, 4 months. I make absolutely no apologies for the pun in the title.

Data dive: Every Ghost Story is a Love Story

"Ghost Story" was the first story I wrote after an almost decade-long hiatus from writing fiction. (Grad school, life, etc.) Psychopomp Magazine published it this fall (it did place, but did not make the cut in Fiction Desk's Ghost Story competition.)

The story is very much inspired by the rowhouses that line many streets in DC. If you've never seen one, they tend to be strangely narrow but deep, and they are connected directly to neighbors (leading to delightful noise issues at times). They typically have an English Basement (which is more half underground than actually underground) with a walk up to the "first floor." I found these houses delightful when I first moved here, but have since decided that I never want to live in one. Some of the rowhouses in DC date way back, which on the one hand means sometimes long and interesting histories, but on the other can also translate into creepiness. Creaking stairways, wooden floors that "settle," old pipes that make mysterious clanging noises. The potential for ghosts seems high...

Logan Circle rowhouses, picture by AgnosticPreachersKid

As I've lived here for a while, I've become more interested in not-necessarily-politically-related history about the city. Below is an old picture from the National Park Service of Meridian Hill Park (mentioned in the story). Way back when the city was first created, all the land it was eventually built on was owned by one rich dude. Then the hill was used as a vantage point during the Civil War before it was eventually turned into the park. The image below is a bit idyllic; when I was here a couple decades ago, the park had a reputation as a place for anonymous sex, drug dealing, and getting stabbed and stuff. It's a bit cleaned up now (probably all of the above are true, but its nice during the daytime and kids play soccer), but there definitely isn't neatly trimmed topiary or lily pads last time I checked. One of the things I would love to do via fiction is highlight that side of DC that is not the DC you see on TV. On the one hand there's House of Cards and All the President's Men. But on the other, there are tons of people that you never see on your TV or in your standard "The corruption goes all the way to the top!" thriller. My friends are teachers and medical professionals, security folks and all kinds of lawyers, IT people, chefs, and artists. There are people who never wear suits and people who sport them every day. And you live in this weird city where occasionally you're stuck in your car and hangry because the traffic holdup is a motorcade, where you might bump into a Supreme Court justice, or where people say "well if we get nuked we'll be first, so we won't feel it." Anyhow, add this story to my collection of DC stories that have nothing to do with politics.

NPS.gov

Number of submissions: 44. Ratio of positive feedback to number of submissions: 27%. Time from completing story until publication: about 3 years. Lesson to be learned: if you keep getting positive feedback on a story, keep sending it out. I'm happy this one found a home. The title actually is a reference to the David Foster Wallace biography, but the story isn't about him. (My friend came up with the inverted title, which I thought was clever, so I kept it.)

In which I am on the top 100 Bestselling Kindle Singles list

I had to take a screen shot because I will probably never get to be on the same page as Stephen King (my idol), Jennifer Weiner, and Alexander Mccall Smith, all who have insane numbers of fans. This is for fiction Kindle Singles.

Proof that this actually occurred!

I actually have no idea how this happened. "Twelve Years, Eight-Hundred and Seventy-two Miles" was published last fall, but there's been a bump in interest in the past few months. I'm currently waiting on the data to see how many copies were actually sold/ downloaded. What chicanery goes into calculating these ranks? Who knows. Being the obsessive person I am, I have been checking it a lot the past few days. Within an hour of posting this, it will probably hop down to 400 or something. But hey, for the next hour, this is where I'm hanging out.

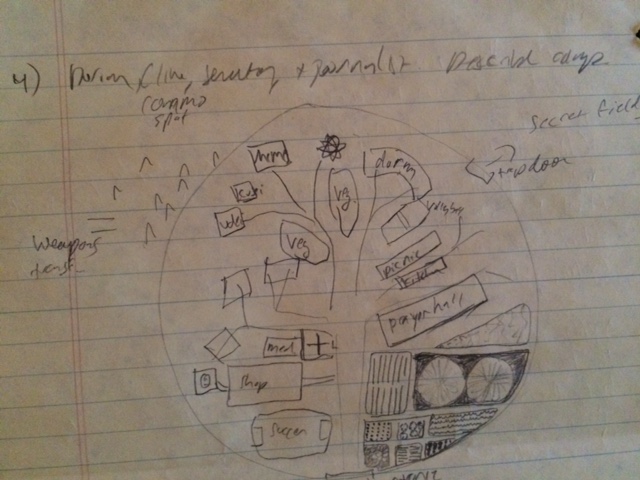

World Building: Draw a Map in Your Awful Serial Killer Handwriting

At one point, I was writing about a small liberal arts school in New England that had been taken over by an armed cult. When I was in high school this was the liberal arts college I had in mind—an amalgamation of every New England liberal arts school (minus the armed cult part). Brick buildings with ivy growing on them, huge fields of green grass, a more or less enclosed space. Somehow every single school I went to ended up being a city campus which probably is the best match for my personality, although when I was in graduate school and had a brief flirtation with becoming a professor, it was those campuses I was thinking about. Small, enclosed, green grass. Quirks I saw during a brief stay at Middlebury: the aggressive sign in the cafeteria which said “Please do not take the lunch trays—THAT’S NOT SUSTAINABLE!” (Presumably people were taking them to go sledding.) Also there was one main street “in town” that had one bar that everyone would go to.

For the book I was writing, why bother going with a real school when I would make up my own and therefore have all my own rules (they can take the lunch trays whenever they want!!) Particularly in stories that take place in an enclosed space, knowing where everything is—and having your characters know this intuitively without them figuring it out on the page—is critical. How big is campus? Where do people live? Where do they eat or congregate after class? Where did that kid get caught having sex in the bushes by the campus police? Where’d they find the dead girl? Where would you hide a gun where no one would find it? How far do random pairings of characters live from each other?

Yup. That's a croissant stain. Deal with it.

I’ve been working on a lot of things at once recently, but have wanted to get going on this speculative fiction thing I’m writing which is sort of like a literary/scifi retelling of the Jonestown Massacre. So I more or less know the beginning and the end. Our heroes arrive at a commune where family members have claimed that abuse is occurring. It’s an enclosed space. I know that things start out fine—the commune seems idyllic and people play volleyball and have plenty to eat. Then things go horribly wrong. How and where do they go wrong? I didn’t have a pre-set idea of things already arranged in my head like I did for the college story so I figured I would start to draw a map and maybe fill things out. I mean, if I were building a commune, where would people eat? Sleep? Where’d they bury the dead girl? Where’s the fence weak? Isn’t that an incredibly small area to grow crops for a commune that is allegedly self-sustainable..?

Points for anyone who can actually read this.

Pushcart Nomination... Not too shabby!

Southern California Review has nominated "Whatever Happened to the Six Wives of Henry the VIII" for the Pushcart Prize. Will I win? No. It made me grin like an idiot though. And that's a good thing.