I've been thinking a lot lately about the novel Middlesex by Jeffrey Eugenides. Specifically what would have happened if that book came out now, and not in 2002. The book received high praise and won the Pulitzer Prize that year. I read it a long time ago, thought it was well-written, and never really thought much about the identity of the author, other than the fact that he seemed looped in with Greek culture. If this book came out now, there would be open questions about a non-intersex person writing about an intersex main character. On the one hand you have the "anyone can write about anything, otherwise this isn't free speech"sombrero camp and on the other side you have the "should he be the person to write this story?" camp. (Some in the latter camp don't write it at all, while others in the latter camp aren't saying don't write it, but"if you do write it, prepare to be scrutinized," or "write it, but should this get preference in terms of publication?") My gut feeling about this of late is something like, Eugenides can probably write about a variety of things really well, so why write this particular thing, and we can consider that having an actual intersex author writing about an intersex character does two things: it checks the "representation box" in terms of diversity but also--and I wish people talked about this more--they would bring value-added that no one else can, even a smart person who is a great writer and how is really empathic. I'm not arguing that any minority writer writing about their own group--regardless of level of talent--is better than an incredibly talented writer writing outside his group. I'm actually making a point about due diligence, taking up space in a market that has limited space, and just plain demographics.

I think anyone can write about anything as long as they are willing to do the homework.* Did he do the research? Did he read stuff by and about intersex people? Did he get intersex readers? Did he write responsibly (ie, not falling back on lazy stereotypes) and with good faith (ie, not assuming automatically that he already knows everything there is to know)? If you're writing outside your own group, particularly if you are writing about a minority group, obviously the answer to all these questions should be yes. (*Apparently this isn't yet obvious, given that we continue to see truly cringe-worthy instances of stuff getting through multiple hoops of the publication process with serious issues).

My take on this is that if your elevator pitch of the book includes the identity, the question isn't "Can I write about this?" but "What do I add to this conversation?" The elevator pitch of Middlesex literally revolves around the main character being intersex. Does the value-added of Jeffery Eugenides go above and beyond what could have been provided by an intersex author? It's the difference between someone writing about their own real world experience and the very real hardships of their life, and someone who is just imagining it. Someone who is thinking, "Ooooh, you know what would be neat to write about?" Identity as a jacket that you can put on and take off when you're done. But some of us can't take off our jackets. I'm not saying an author shouldn't do this at all--the guys that wrote The Wire were often writing about people who were not like them. But they were writers who really, really knew the environment (one was a former homicide detective and the other a former police reporter), and wrote the characters with multiple dimensions. The problem with making this call--Do I know enough?--is that people who are not competent often have no idea of how incompetent they are.

Here's a completely arbitrary diagram about writing outside your identity about other people's groups.

Given that we continue to live in a world where people say "I already have a [insert minority] client" and "I already have a [insert minority] book," I'm going to look at the top left corner here and think, no. I was recently listening to a podcast of people who work in the publishing industry and the hosts were really excited about ARCs of some new books they had just gotten which had diverse characters (they had specifically wanted to read more diverse books). Then a few moments later they realized that they were not books written by people from those groups. It's fine to write about people from other groups if you do it well, but it's not fine for us to be pleased about increased diversity in books if it doesn't mean actually making publishing more diversely (accuracy [sensitivity] readers make money being accuracy readers for other people writing books about the groups they belong to, rather than the industry actually publishing books by people like the accuracy readers themselves). If a book is fundamentally about identity, there's still an issue of "There can only be X number of books about that" in any publisher's given catalogue for year. Are you taking space away from someone else? Is it the case that your book about--I don't know--blackness, written from the perspective of someone who is not black, is a little more palatable to non-black gatekeepers, because maybe there is content from actually black people that might make them uncomfortable, that might be a bit too dark, that might be a bit inaccessible? I'm not here to read a Toni Morrison book to have everything be accessible to me--it doesn't have to "speak to me"--it's not about me. (Incidentally, there seem to be a lot of fantasy and scifi books where there is some arbitrary category that serves as a stand-in for race wherein the reader, often so someone who doesn't belong to a particular group can learn an important, ham-handed lesson. But at least right now I think there are some very real lessons about real groups in the real world that not enough people know about.)

More importantly, at least consider the question, what is your value-added as an outsider? I am unabashedly a huge fan of all the Rocky movies. So when I heard Creed was coming out a few years ago I was super excited. I didn't want any spoilers so I consumed no media about the movie whatsoever. I'm someone who, when I'm watching a movie, completely gets absorbed in it (as long as some asshole in the theater isn't chewing loudly) and forgets about my own existence. But then something happened that completely broke me out of the reverie. It's a scene where Michael B Jordan is talking to Tessa Thompson and they're flirting. I was completely pulled out of the movie because I suddenly realized, Oh, a black person wrote this. I had assumed that Sly Stallone had written it, because he's written all the other Rocky movies. This isn't a dig about the movie--it's just that I saw the movie with the expectation that Stallone had written it and there was a cadence and feel to the dialogue that was so distinct to me that I suddenly had that realization. The writer was Ryan Coogler, the same guy that just made Marvel nine babillion dollars with Black Panther. Maybe having black people write about black people works? As the child of parents who immigrated to this country from the Subcontinent, there are parts of Kiran Desai's The Inheritance of Loss about leaving home and immigration that were so acutely accurate that they were painful, and in a specific way that I think non-immigrants might have just felt "that was sad" and not "you're poking an awl straight into my soul in a place where I can't even articulate." There is stuff about being female in Elena Ferrante's Neapolitan novels that just describes the intersection of all the roles you have to play as a woman so perfectly, I don't think someone who wasn't female could have written those books and I don't think any man reading them would have shouted "Yes!" when they got to those parts. I can always, always tell if an author actually has a dog because they will write about a character with a dog where either the dog does some weird, very specific doggy thing, or its human interacts with them in some particular odd interaction--verisimilitude-- I guess that is the word I'm looking for. There is a peculiarity to verisimilitude, a specificity you can't hit sometimes unless you really really know that life.

So if you're not in the group, and your work is focused on identity... I have to ask, what is your value-added to this conversation? If the group is small on top of that, who are you displacing?

The population of America is roughly 325 million. Let's just say arbitrarily that 10 million are writers. Most traits fall into a normal distribution (bell curve) where the bulk of people are average, and a small percentage are exceptionally good. Note I said percentage, not number. Let's take the top 10% of talent and say they are the contenders for publication. (In reality, it's probably more like the top 30%. You have people who are almost universally recognized as talented way at the top, but then you have people that are just good enough to tell a story and sell airplane books.)

So you have 1 million writers who are exceptionally talented. Let's consider a small population-- Native Americans, 1.3% of the population according to the Census. Assume (for the sake of argument) that they are randomly distributed in terms of talent (ie, that there is no reason to believe that Native Americans are exceptionally good or bad writers.) That leaves you with 10,000 Native American writers who are exceptionally good. So for the 990,000 other exceptionally talented writers, you're good enough to get published anyway, do you need to tell a story that focuses on Native American identity? But then go back and consider that they might not be proportionally represented in the population of writers because of lack of access to good education, health care, etc., which would take some out of the pool of potential writers. So there's even fewer of them. Consider that Native American writing about identity might literally be focused on displacement and erasure. At least consider it.

The larger the group gets, the more absurd it seems to question whether or not people should write outside their group. Plenty of men write women well, and vice versa. I'm more likely to roll my eyes or laugh when they get it wrong than I am to be offended. (Unless they do a shitty job and people congratulate them on how good a job they did--not naming names here ;) I write male characters, but have no interest in writing a book that fundamentally revolves around maleness. Probably just because I'd be asking myself what I would be bringing to the table. Different if you are literally an expert in that thing: I had a friend once who got her doctorate in history about a very specific period in Vietnam's history on the interaction between the French and the Vietnamese. She spoke French and Vietnamese but was of neither descent. She read historical texts about that time period in three languages. She had lived in Vietnam. Had she been a writer, I'm convinced she would have both done a good job representing the culture and--because she is reasonable--would have gotten herself the appropriate readers. She wasn't saying, "Oooh cute!" and pulling on a jacket. She had her doctorate in that jacket. She did the time, that is to say.

Jonathan Franzen once gave this interview to Slate where he said something ridiculous and people got so spun up about the ridiculous thing that they missed some peripheral things he was saying that were really really important. The part people got spun up about was JFranz saying that he wasn't well-placed to write about race--blackness, specifically--because he doesn't have very many black friends and has never been in love with a black woman. His lack of diversity in friends aside, he also said this: "I feel it’s really dangerous, if you are a liberal white American, to presume that your good intentions are enough to embark on a work of imagination about black America." This, exactly. Good intentions are not enough. But I also think both of his comments are basically saying this: Don't write what you don't know. And the more controversial the thing is, the more likely you are to make an ass of yourself. All eye rolls aside, I think he's right about the friends thing--not that "I have a gay friend" gives you license to write a gay character, but that you might not know what the fuck you're talking about if you've never had a gay friend. I'm comfortable writing about characters that grew up in mid-Atlantic suburbia, live in a handful of cities I've actually lived in, eat the things I eat and read the things I read--anything else and I'm going to be anxious enough to be doing a lot of research. It takes a certain level of audacity to presume you can write about an identity without actually knowing it. In the literally limitless universe of things to write about, why is that one specific thing the thing you have to write about? I'm not saying don't do it, I'm saying ask yourself the question why.

But going back to the two by two box--the bottom row specifically. I want to make an argument for diversity for diversity's sake in stuff that isn't about identity, even if it's pretty thin. In a perfect world, all characters would be three dimensional. The reality is that some books are airplane books that are fluff fluff fluff and aren't going to talk about serious and controversial issues, and some characters--major or minor--don't have a story about identity to tell. But about that idea of verisimilitude: I have lived in several major cities that writers often write about, and I think it is unconscionable when these cities are depicted as entirely white (or entirely wealthy, for that matter). New York City is insanely diverse across every possible dimension. DC is a black city. A version of LA that does not acknowledge the existence of its massive Spanish-speaking population is absurd, and the same can be said of east Asians in San Francisco. I'm not saying just throw in a minority neighbor or something, but think about what it means if you've written an Asian-less San Francisco. Imagine writing a novel about an NBA player who is white--sure there are white NBA players, so this is fine--but imagine you depicted the NBA writ large as all-white. Why would you specifically choose to do this?

If a minority character's main purpose is finding the treasure, killing the bad guy, whatever, their minority identity isn't really relevant. You don't need to write some deep treatise on race. I can think of two good examples where racial identity of minority characters was pretty thin and I didn't care. I read a good chunk of "James S. A. Corey's" Leviathan Wakes, which is the first book in The Expanse scifi series. James S. A. Corey is actually a pseudonym for two ostensibly white dudes. Anyhow, they have a multiethnic cast of characters, which makes sense because when the distant future is depicted as all one color, you wonder if a bunch of genocides happened (or at least I do). So there's brown people but they lack race consciousness (IMHO), which is fine because it isn't really necessary to tell that particular space adventure story. This isn't a story about the implications of race played out in the future ala Octavia Butler.

Sleepy Hollow is a ridiculous but fun show with a very mixed cast. The main female lead, Abbie, is black, but the show isn't about blackness. It focuses on her chasing down various ghoulies with Ichabod Crane, who has been pulled out of pre-Revolution America into the present. This results in some fun fish-out-of-water scenes (eg, Ichabod is outraged by men wearing hats indoors!) At one point Abbie is sent back to Ichabod's era where even walking around is inherently dangerous for her. She could be rounded up at any moment as a random, unaccompanied brown woman, and possibly sold into slavery. The show didn't have her stay there too long--I thought there were a lot of other interesting things they could have explored but didn't. I wasn't annoyed, but if there were some nuanced nod to race, I would have been impressed with the writing. But I'm not expecting to be impressed by the writing on a show like this.

A note about research and getting readers:

I strongly believe that we should get rid of the term "sensitivity reader." It brings to mind someone rolling their eyes and saying, "Quit being so sensitive!" I'm not being "sensitive" when I'm annoyed when a popular author, writing through the POV of an Indian woman, references the fact that she "speaks Indian" (sidebar: they speak hundreds of languages in India, none of which is called "Indian." A quick Wikipedia search could tell you that.) This pulled me way out of the story in a bad way. It made me think about how the author's readers, agent, editor, copyeditor, and god knows how many other people never bothered to Wikipedia that shit. This is a petty example, but there are worse ones out there. It's the lack of humility and intellectual curiosity to at least wonder, "Hey, did I get this right? Maybe I should ask someone who would know..."

I wrote a novel that takes place in Boston. I visited a few times, took pictures, looked stuff up, poked around MIT. It's called due diligence. If you're writing about cops, you should research ops. For some reason, saying "don't be sloppy writing about cops" is okay but if you're accused of being sloppy writing about race or disability or whatever, suddenly it's censorship and an infringement upon your rights. We all have permission to be sloppy, we just don't have the heart to be criticized for it and talking about these really awkward things is something America is not good at. In fact, we are catastrophically bad at it. On the other side, right now I don't think people have the emotional energy or patience to be kind in their criticism sometimes. Malicious intent is often assumed; I'm not a believer in the "intent doesn't matter" argument because this likens manslaughter to first degree murder. This makes for a lot of skirmishes.

Repeated rejection can be soul crushing, resulting in even exceptionally talented writers giving up. Imagine if on top of that standard level of soul-crushingness you were told "Black people don't buy books" "This book is too gay" or "I already have an Asian book." (Yes these are all things that have actually been said to people.) All of these things are either factually incorrect or subjective judgments not backed up with meaningful data. Not only are they offensive to people in those groups, but offensive to the assumed straight white reader. Straight white people bought The Kite Runner, The Hate U Give, and Sing Unburied Sing by the millions. Are we to believe that The Diving Bell and the Butterfly would never sell because there aren't enough bed-ridden eyeblink people to form a market??

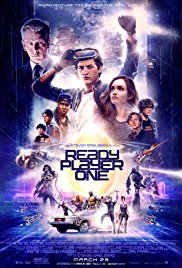

This failure of imagination is the same reason why we keep having the same dumb movies rebooted over and over while for decades people didn't have faith that a woman could direct a big-budget action movie (like Wonder Woman), or that audiences would be willing to get behind black leads (like Black Panther). Think of all the original material we could have consumed, and that people could have made money off of if they hadn't had that failure of imagination.

Further reading:

Kaitlyn Greenidge's essay on this, if you haven't already read it.

Two articles on this cluster: Vulture and WaPo

One of the most bizarre hoaxes and a case of appropriation, the story of "JT LeRoy" also made into a good documentary you can stream, Author: The JT LeRoy Story.

Humorous article about women responding to how men write about women.